QuestDB 6.2.0 brings a brand new JIT (Just-in-Time) compiler as a part of the SQL engine. The compiler aims to significantly improve execution times for queries with simple arithmetic expressions used to filter the data. It took us 11K lines of code, 250+ commits, and plenty of coffee to ship it, and we'd like to share the story with you.

Before we dive into the implementation details behind our JIT compiler, let's understand what kind of problems JIT compilation aims to solve in our SQL engine and where exactly you should expect performance improvements.

It can often happen that analytical queries run by users end up performing a full scan over a table or, at least, over some of its partitions. Here is an example of such a query:

SELECT *

FROM trips

WHERE pickup_datetime IN ('2009-01') AND total_amount > 150;

The above query returns relatively expensive trips within one month from 10+

years of taxi data available on our live demo. To

execute this query, QuestDB has to scan 13.5 million rows. This means that the

database has to do many sequential reads from the column files and apply the

filter expression (think, WHERE clause) to each value. There is a good chance

that the data is already in the page cache or the disk is fast enough not to

become the bottleneck. Thus, the execution time for such queries has all chances

to be limited by the CPU performance.

The pre-JIT implementation of filter expression evaluation in QuestDB is based on the operator function call tree. The functions are nothing more than Java classes you may find as part of the Griffin engine. This approach is quite powerful and general, but it also has some disadvantages we will cover.

Pre-JIT filtering

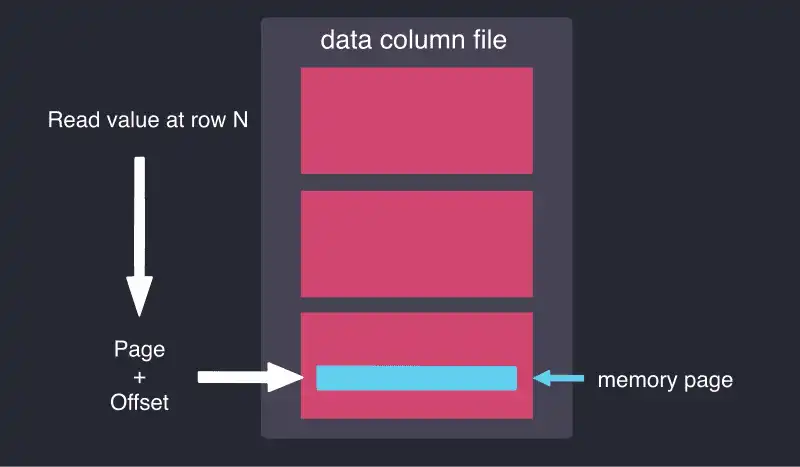

As you may already know, QuestDB has a column-based storage model. Data is stored in tables, with each column stored in its own file. For read-only queries, columns with fixed-size data types are read by translating the record number into an offset in the column file by a simple bit shift. The offset is then translated into an offset in a lazily mapped memory page, where the required value is read.

This storage model allows queries that do a full or partial table scan to be performed efficiently. The database interprets the filter expression during the query evaluation, translates it into an operator function call tree, and then executes the query in a tight loop. In the case of our example query, the loop looks something like the following Java code:

public boolean hasNext() {

while (base.hasNext()) {

if (filter.getBool(record)) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

This method is called when the database iterates through the result set to send

the query result to the client. Here, the filter is the top-level object from

the operator function call tree that we've mentioned. The base is the data

frame cursor responsible for the iteration through the column files, and the

record is the flyweight

object that allows accessing column values for the current row. The call tree is

minuscule in our example and only consists of three objects.

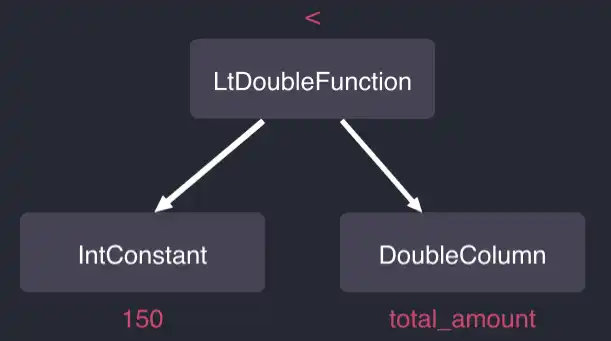

The top-level object called LtDoubleFunction is our filter object. This

function is a comparison operator while IntConstant (the 150 constant

literal) and DoubleColumn (the total_amount column) are its operand

functions. Notice that the pickup_datetime IN ('2009-01') part of the query is

not present in the filter since QuestDB is smart enough to apply the predicate

for the

designated timestamp

column (pickup_datetime) to the underlying data frame cursor and remove it

from the filter tree.

As you might have already guessed, the filter.getBool(record) method call from

the Java snippet calls the filter tree hierarchy for each iterated row. When

called, LtDoubleFunction calls its operand function to obtain their values on

the current row, compares them, and returns the filter result to the outer loop.

The hierarchy and the number of nested calls may be arbitrarily large for

complex SQL queries. JVM's (Java Virtual Machine) own JIT compiler does a great

job optimizing the code, but it's possible to produce more efficient machine

code in this particular case. As we find out later, the difference between JVM's

JIT output and our own machine code may be noticeable even for simple queries.

Another sub-optimal aspect here is that this way of filtering is "scalar", i.e. it navigates through the table row by row and applies the filter to a single row at a time. In many cases, the execution of the filter expressions could be accelerated by vectorized processing when SIMD instructions are used to calculate the filter result for multiple rows simultaneously.

Accordingly, we built the JIT compiler to solve the above problems and improve CPU usage efficiency for a certain class of SQL queries.

JIT-based filtering

QuestDB's JIT compiler consists of two major parts: the frontend and backend. The frontend is written in Java and kicks in once an execution plan is built for the query. Frontend's primary goal is to analyze whether the filter is suitable for JIT compilation and serialize the filter abstract syntax tree to an intermediate representation (IR) along with necessary metadata. The IR is then provided in a call to the backend, which finishes the compilation and emits compact and efficient machine code for the filter function. When vectorized execution is enabled, the filter from our example trips table query compiles to 58 machine instructions.

The compiler backend itself is written in C++ and uses asmjit library for machine code generation. Currently, the backend works on x86-64 CPUs only and uses AVX2 instructions in the compiled function when the CPU supports them.

The filter function is called on table page frames instead of individual rows. When the function uses SIMD instructions, the CPU core executes the query processes multiple rows simultaneously. For instance, for a filter on a single INT (32-bit signed integer) column, 8 rows would be processed concurrently since AVX2 registers are 256-bit. Once the filter result is calculated on these rows, their row IDs are appended to an intermediate array. Later, when all rows in the page frame are processed, the array is returned back to the Java code. This way, we can benefit from batch processing and vectorized execution.

Apart from the supported CPUs, there are a few limitations in the first release of the JIT compiler. Only filters with arithmetical expressions for fixed-size columns are a subject for the compilation. We will expand the functionality of the JIT compiler in future releases.

How to use it

SQL JIT compiler is a beta feature and is disabled by default. To enable it, you

should change the cairo.sql.jit.mode setting in your server.conf file.

cairo.sql.jit.mode=on

Embedded API users are able to enable the compiler globally by providing their

CairoConfiguration implementation. Alternatively, JIT compilation can be

enabled for a single query by using the SqlExecutionContext#setJitMode method.

The latter may look like the following:

final CairoConfiguration configuration = new DefaultCairoConfiguration(temp.getRoot().getAbsolutePath());

try (CairoEngine engine = new CairoEngine(configuration)) {

final SqlExecutionContextImpl ctx = new SqlExecutionContextImpl(engine, 1);

// Enable SQL JIT compiler

ctx.setJitMode(SqlJitMode.JIT_MODE_ENABLED);

// Subsequent query execution (called as usual) with have JIT enabled

try (SqlCompiler compiler = new SqlCompiler(engine)) {

try (RecordCursorFactory factory = compiler.compile("abc", ctx).getRecordCursorFactory()) {

try (RecordCursor cursor = factory.getCursor(ctx)) {

// ...

}

}

}

}

When QuestDB starts with the enabled JIT compiler feature, the server logs will

contain messages relating to SQL JIT compiler like the following:

2021-12-16T09:25:34.472450Z A server-main SQL JIT compiler mode: on

2021-12-16T09:25:34.472475Z A server-main Note: JIT compiler mode is a beta feature.

As already mentioned, JIT compilation won't take place for any query you run. To understand whether the compilation took place for a query, you should check the server logs to contain something similar to this message:

2021-12-16T09:35:01.742777Z I i.q.g.SqlCodeGenerator JIT enabled for (sub)query [tableName=trips, fd=62]

Performance impact

To get an idea of the performance improvements you can expect with JIT, we can do some benchmarking. It's important to mention that your mileage may vary since performance improvement provided by JIT compilation depends on many factors, such as exact software versions, hardware, table schema, and query. The below results were obtained on a laptop with i7-1185G7, 32GB RAM, and an NVMe SSD drive running Ubuntu 20.04 and OpenJDK 17.0.1.

We start with the query from our example:

SELECT *

FROM trips

WHERE pickup_datetime IN ('2009-01') AND total_amount > 150;

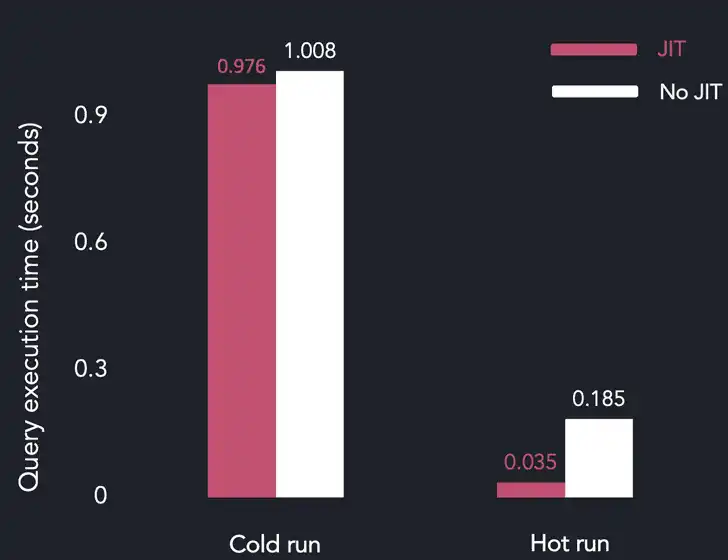

These are the results of the average query execution time observed after several runs (so-called hot query execution). In this case, a "cold run" stands for the first query run, while "hot run" means a subsequent run where the table data is in the page cache.

The results show that the JIT compiler doesn't make any difference for cold runs, i.e., I/O-bound scenarios. Once the data is in the page cache, the query execution becomes CPU-bound, and JIT reduces the time dramatically - by 76% compared with the Java implementation.

If we do some back-of-the-envelope calculations, the on-disk size of the

total_amount column file in the 2009-01 partition is 110MB. Considering that

the query takes around 35ms when JIT is enabled, this yields almost 3.3 GB/s

filtering rate. In fact, it's even higher since the SQL engine also needs to do

other steps when executing a query, like gathering the result set. In addition,

with more fine-grained benchmarks, we saw a filtering rate of 9.4 GB/s on the

same machine, which is not far away from its peak memory bandwidth (24.9 GB/s on

a single thread).

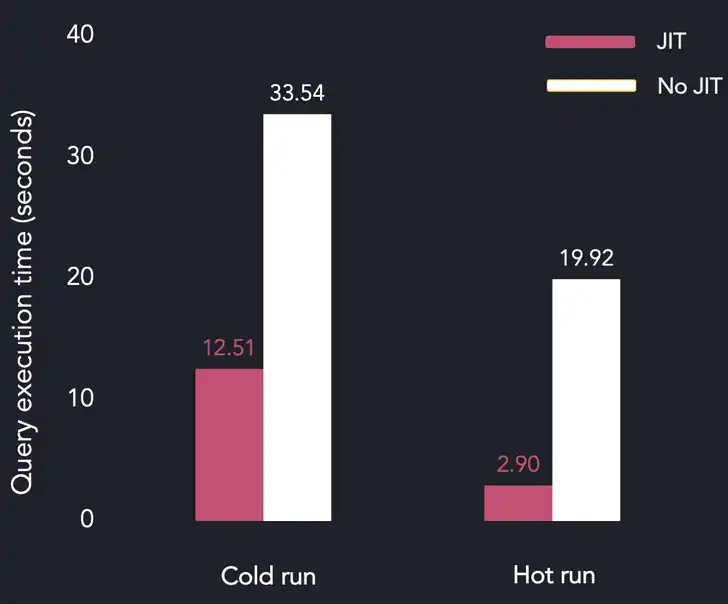

Why don't we make the task much harder? To do this, we can remove the time predicate and run a query for trips with a total amount over a value for a single passenger across all years. This means a full table scan of 1.6 billion rows in total.

SELECT count(), max(total_amount), avg(total_amount)

FROM trips

WHERE total_amount > 150 AND passenger_count = 1;

The measurement results for this query are the following:

Once again, we see a significant improvement when the JIT compiler is enabled, and the data is in the page cache. Interestingly, due to a larger volume of the data that has to be read from the disk, JIT also improves cold execution time.

Next up

This is only the beginning for QuestDB's JIT compiler, and we have a lot of plans for its future improvements. First of all, we'd like to support ARM64 CPUs along with the NEON instruction set. Next, we'd like to parallelize the query execution when suitable to improve the execution time even further. Finally, we plan to expand the limitations on the supported filters and experiment with potential optimizations in the JIT compiler.

We encourage our users to try out the SQL JIT compiler feature on their development QuestDB instances and provide feedback in our Community Forum. JIT compiler is also enabled on our live demo, so you may want to run some queries there. And, of course, open-source contributions to our project on GitHub are more than welcome.